Classic period shipwreck

Peristera

The island of Peristera belongs to the Northern Sporades complex and is located a very short distance east of Alonissos. North of Kokkalia Bay, at a distance of 150m from the coast and at a depth of approximately -23 to -28 msw, the cargo of amphorae from an ancient merchant ship that was wrecked there in the classical era, around 425-400 BC, is preserved on the seabed.

The archaeological significance of the Peristera shipwreck

This shipwreck is one of the most important of classical antiquity. The Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities conducted excavations under the direction of Dr. Elpida Hatzidaki in 1992, 1993, 1999, and 2000. From this research, it is concluded that the ancient merchant ship transported over 3,000 amphorae of wine from two well-known wine-producing cities of the time, Mende in Chalkidiki and Peparithos (present-day Skopelos). Under the numerous amphorae, fine ceramic vessels of excellent quality (black-painted kylikes, bottles, etc.) were identified and raised, which were also intended for trade. Only a few copper nails and small pieces of wood have been found from the ship’s hull itself, some of which bore traces of burning, an element that indicates fire as one of the possible causes of the shipwreck.

The impressive image of the shipwreck, the short distance from the bay of Steni Vala in Alonissos and the accessible depth, were strong motivations for choosing the shipwreck as the first underwater museum in Greece, which has been open to the public since 2020.

The research

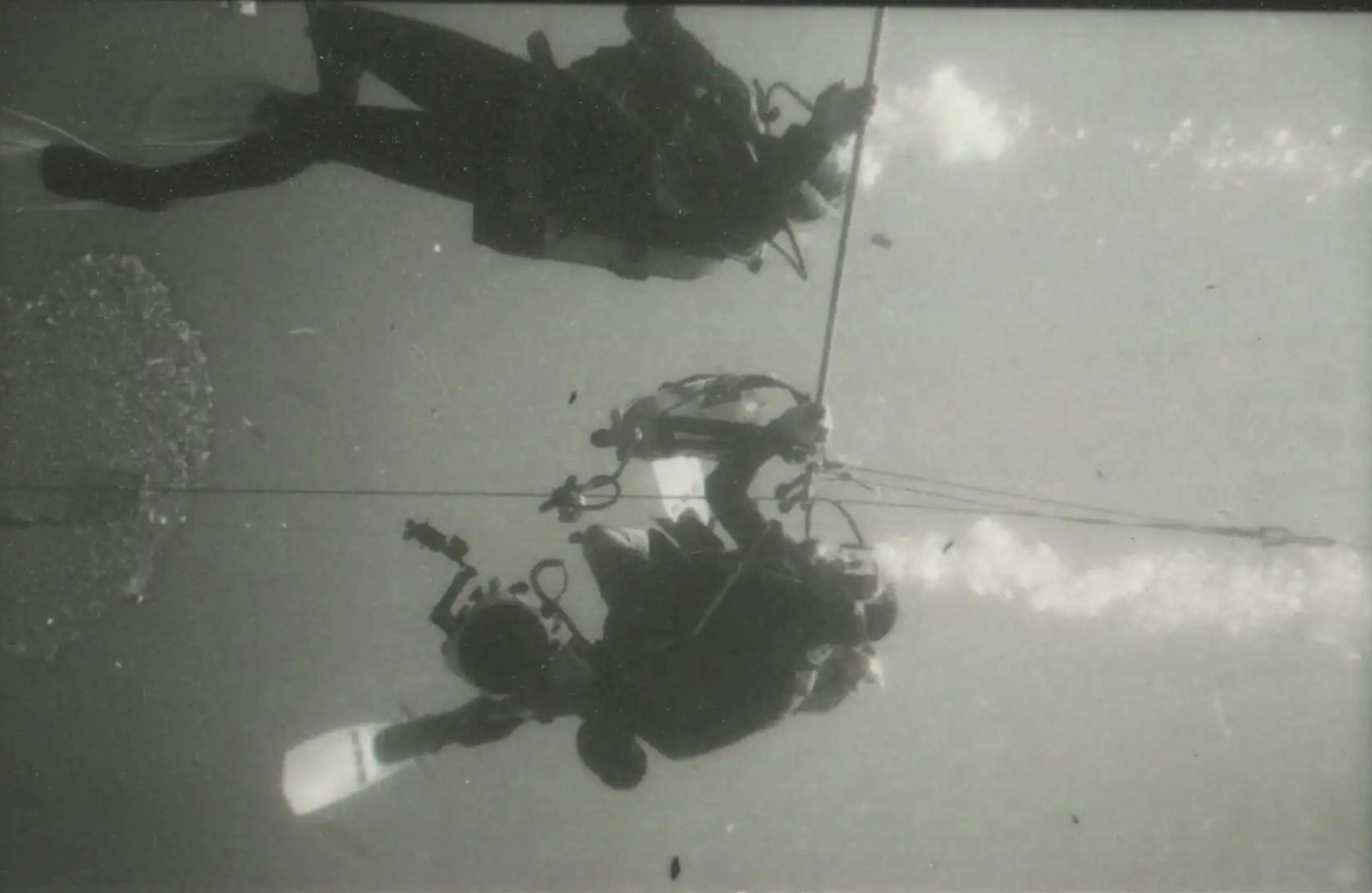

In 1985, local fisherman Dimitris Mavrikis reported to the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities the existence of an ancient shipwreck on the island of Peristera. The then Director, Dr. Elpida Hatzidaki, organized the first reconnaissance survey, which took place in 1991. It was discovered that the ancient shipwreck was significantly larger than the previously known shipwrecks of classical times, and a systematic excavation was deemed necessary.

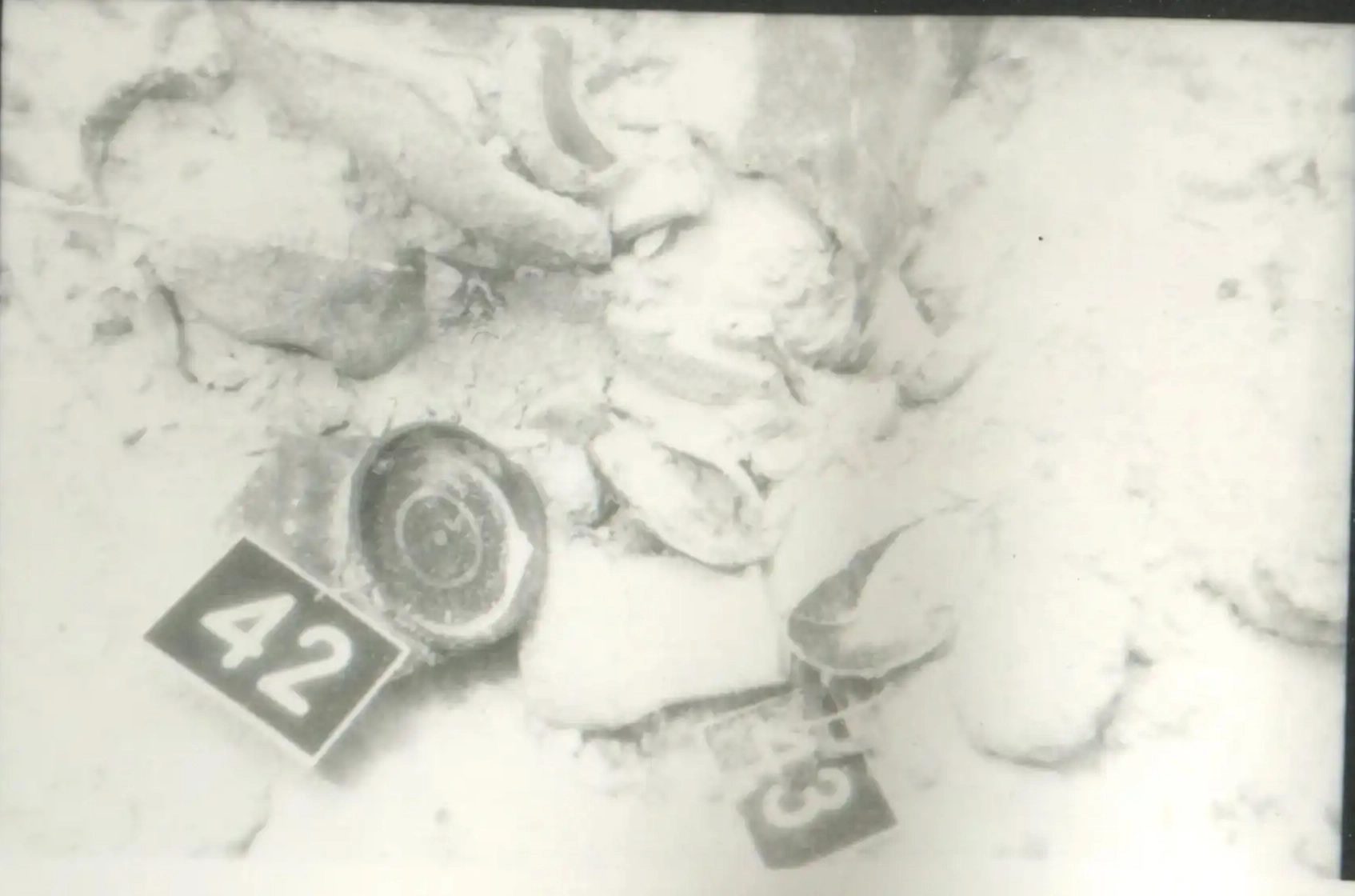

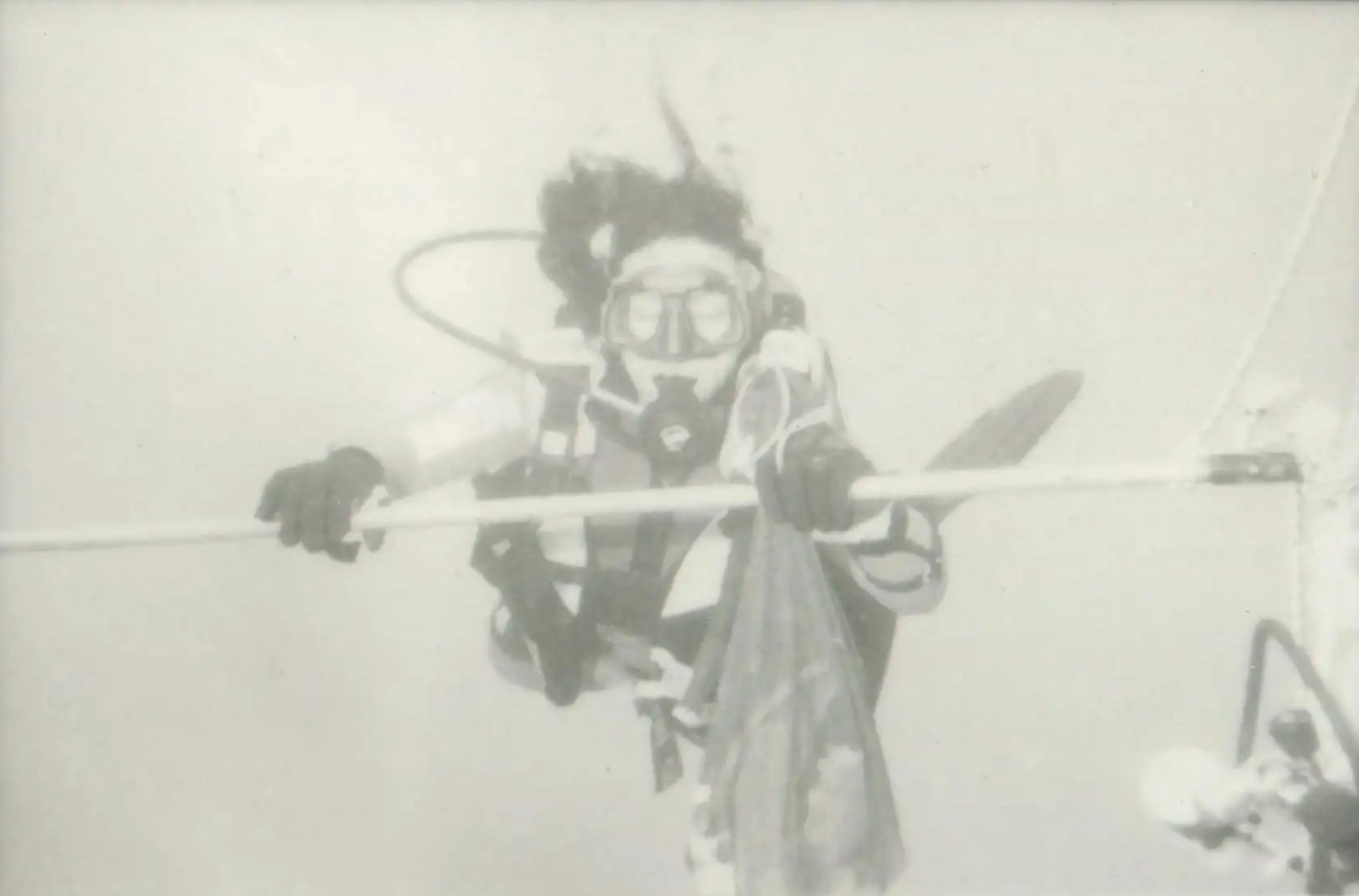

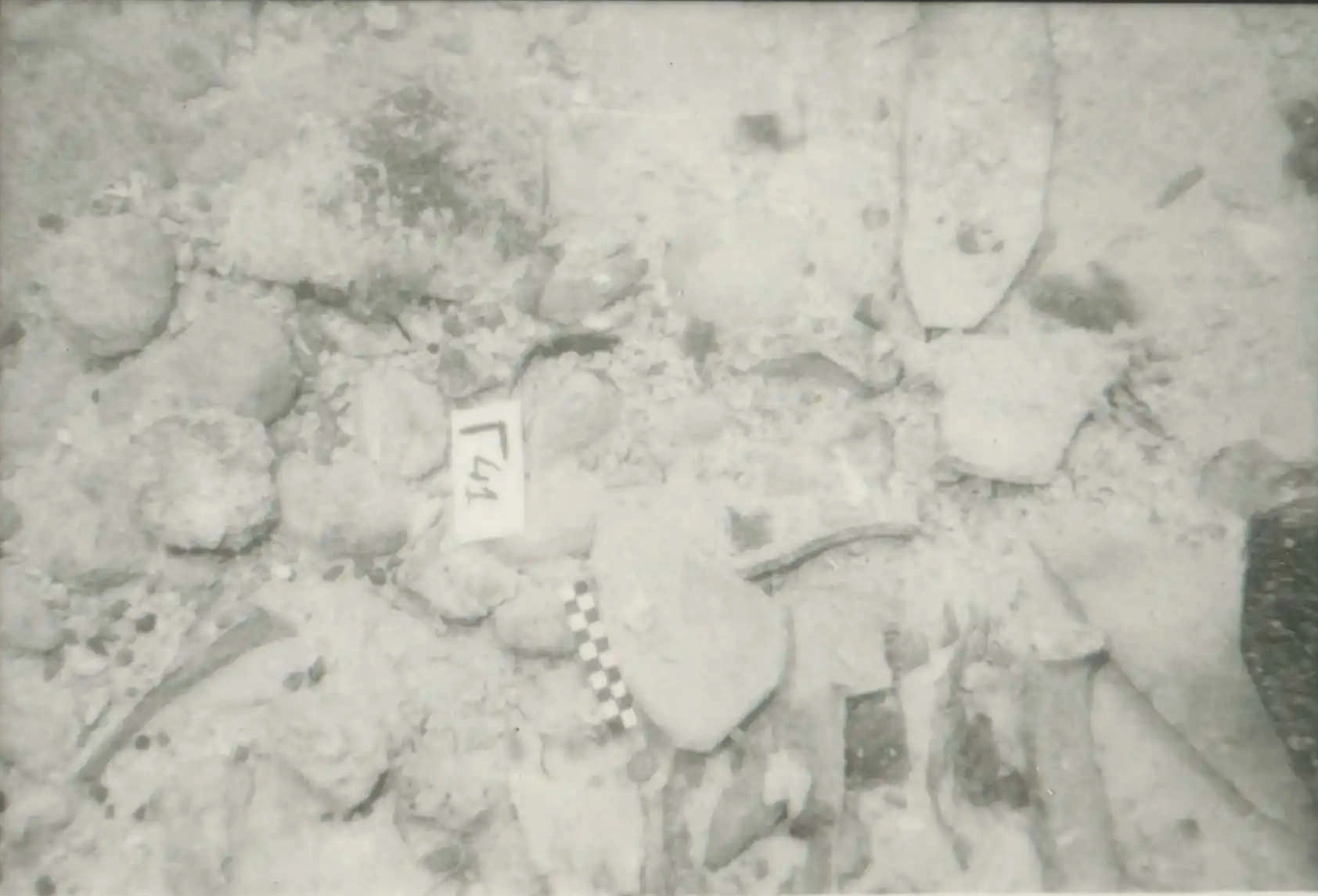

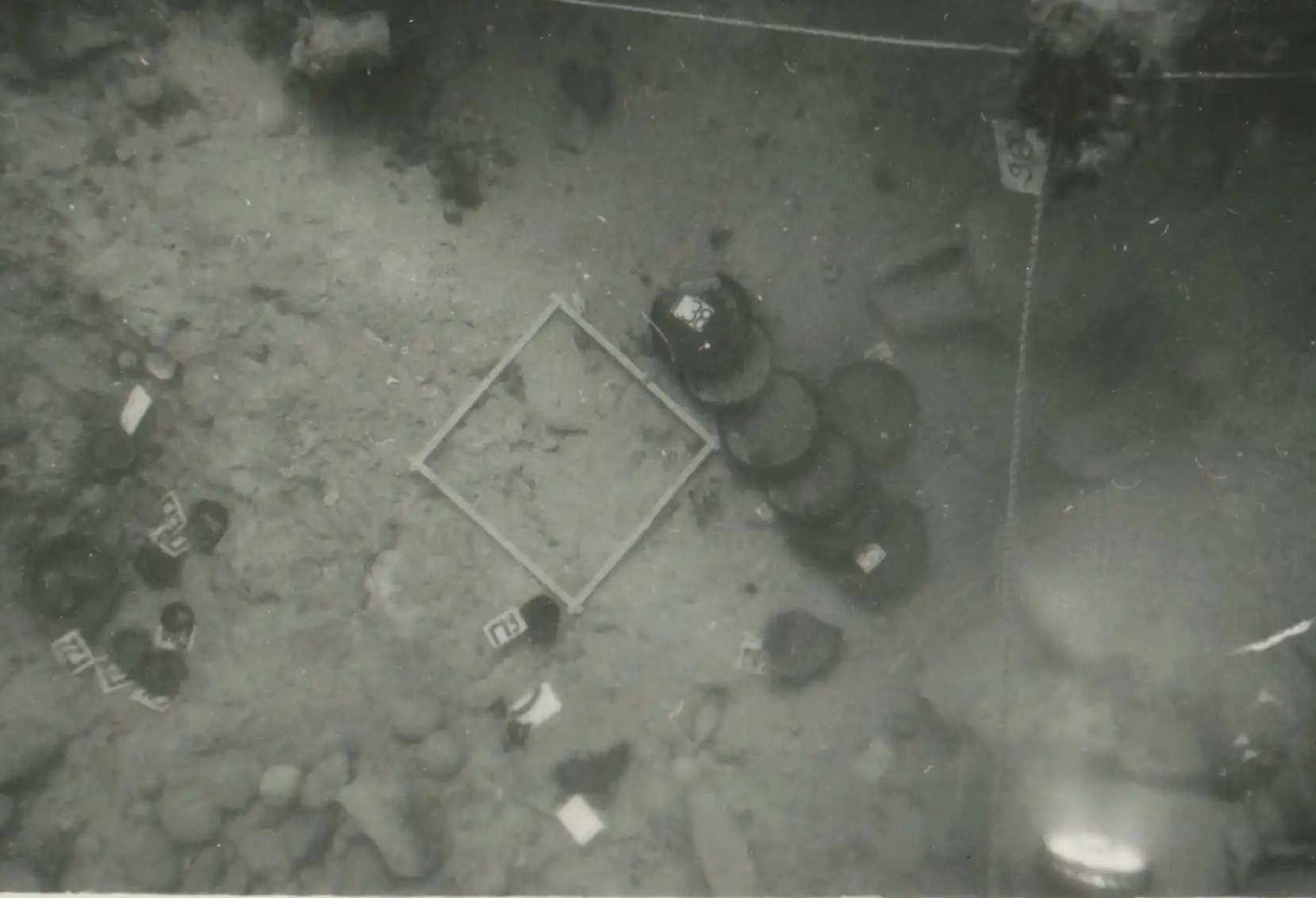

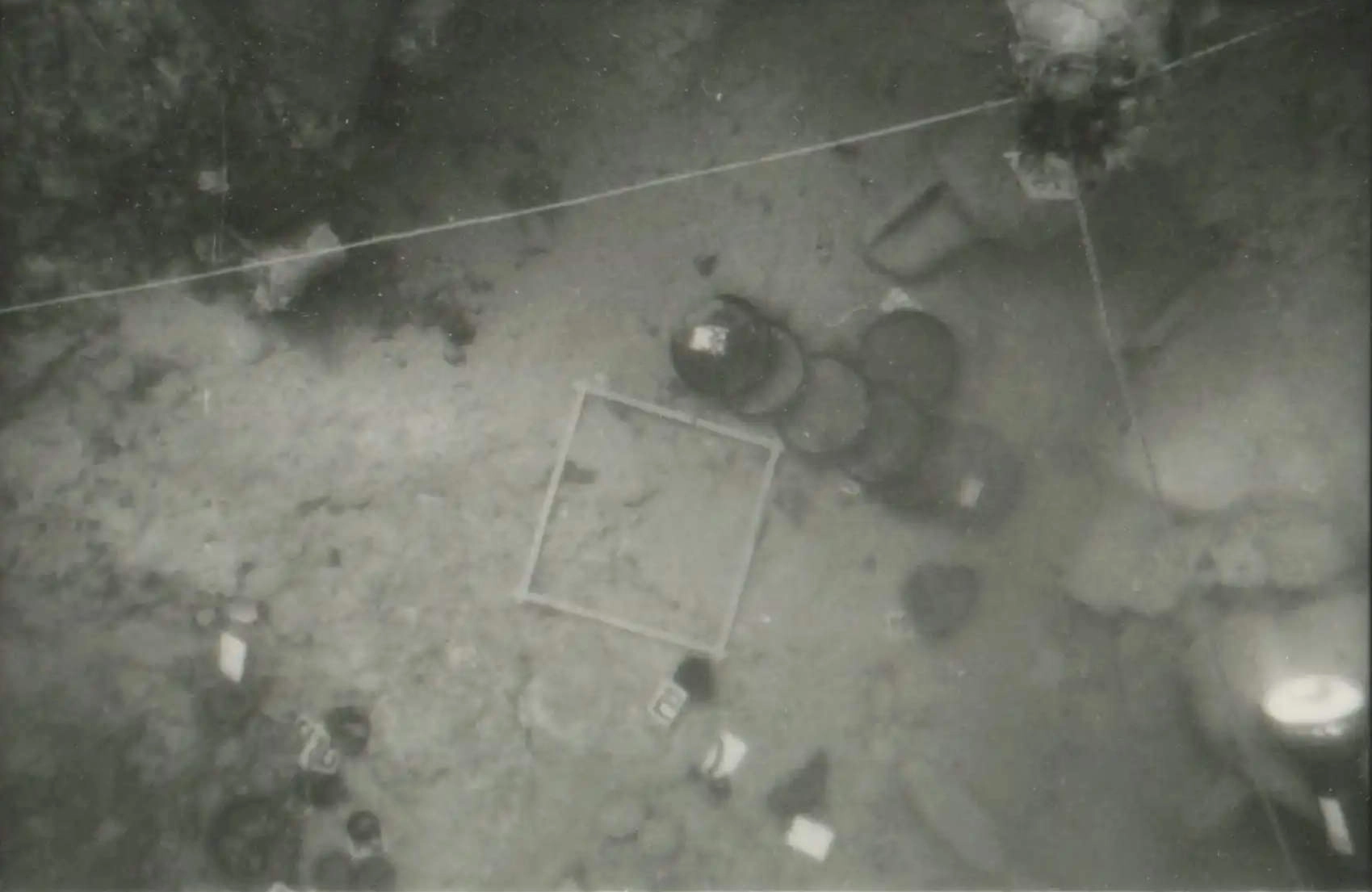

In the four research periods that followed (1992, 1993, 1999 and 2000) the shipwreck was mapped, over 1,000 surface amphorae were counted and an excavation section was carried out, transverse to the longitudinal axis, which showed that the amphorae were loaded in at least three layers, while in the lower layers it revealed very good quality black-painted ceramics (plates, cups, etc.) that are among the ship’s marketable cargo. Vessels used by the crew were also found, such as clay drinking vessels, cauldrons, lamps and a clay mortar (mortar) for grinding food. Only a lead anchor link was found from the ship’s rigging, while no identifiable element has been found from the ship itself, except for a few copper nails and a few small pieces of wood which, however, were dated using the carbon 14 (C14) method and gave a range of shipbuilding dates between 480 and 420 BC.

This research, conducted with the assistance of numerous Ephorate staff, including both regular and temporary personnel from all specialties, and with the support of the Navy, was the most extensive underwater excavation of its time. Pioneering methods of recording were tested for their time. At the same time, scientific conclusions demolished the theory that placed the construction of such large merchant ships much later, in the Roman period, specifically during the 1st century BC.

The ship

Although the hull of the ancient merchant ship is not preserved, the cargo of amphorae, as it has largely retained its cohesion on the bottom, gives us a sense of the outline and dimensions of the ancient ship. The length of the area occupied by the cargo indicates that the boat would have been at least 25m long. The modern (around 400 BC) shipwrecks that have been investigated in Italy (Porticello), Israel (Ma’agan Michael) and Turkey (Tektas Burnu) belong to ships of approximately 12 to 17 meters in length. In contrast, the shipwreck of Cyprus (Kyrenia) from about a century later did not exceed 15m.

From the number of amphorae alone, it is estimated that the ship at Peristera could have carried a cargo of over 120 tons. In comparison, the equivalent at Porticello is estimated at 30 tons.

In ancient sources, merchant ships were generally called “Round ships”, as the spacious holds gave curved lines to their hulls, in contrast to warships. Specific types of ships are also mentioned, such as the larger olkas and kerkouros, as well as the smaller kelis, akatos and lemvos.

Merchant ships did not need large crews, since the primary means of propulsion was the square sail on a central mast. However, there is pictorial evidence from the 5th century BC showing a second auxiliary mast with a smaller sail (artemon) near the bow.

The ship’s steering was achieved with two large side rudders on either side of the stern. To protect the ship’s hull, they used a lining of lead sheets. At this time, the most common type of anchor was made of wood, with its connection reinforced by a metal joint (collar). The counterweight (stypos) consisted of either a stone cleat or a wooden cleat with lead cores. A lead cleat was found near the shipwreck of Peristera. Ancient writers refer to the sacred anchor as the most prominent anchor carried by a ship, and it was guarded as a last resort to prevent collisions.

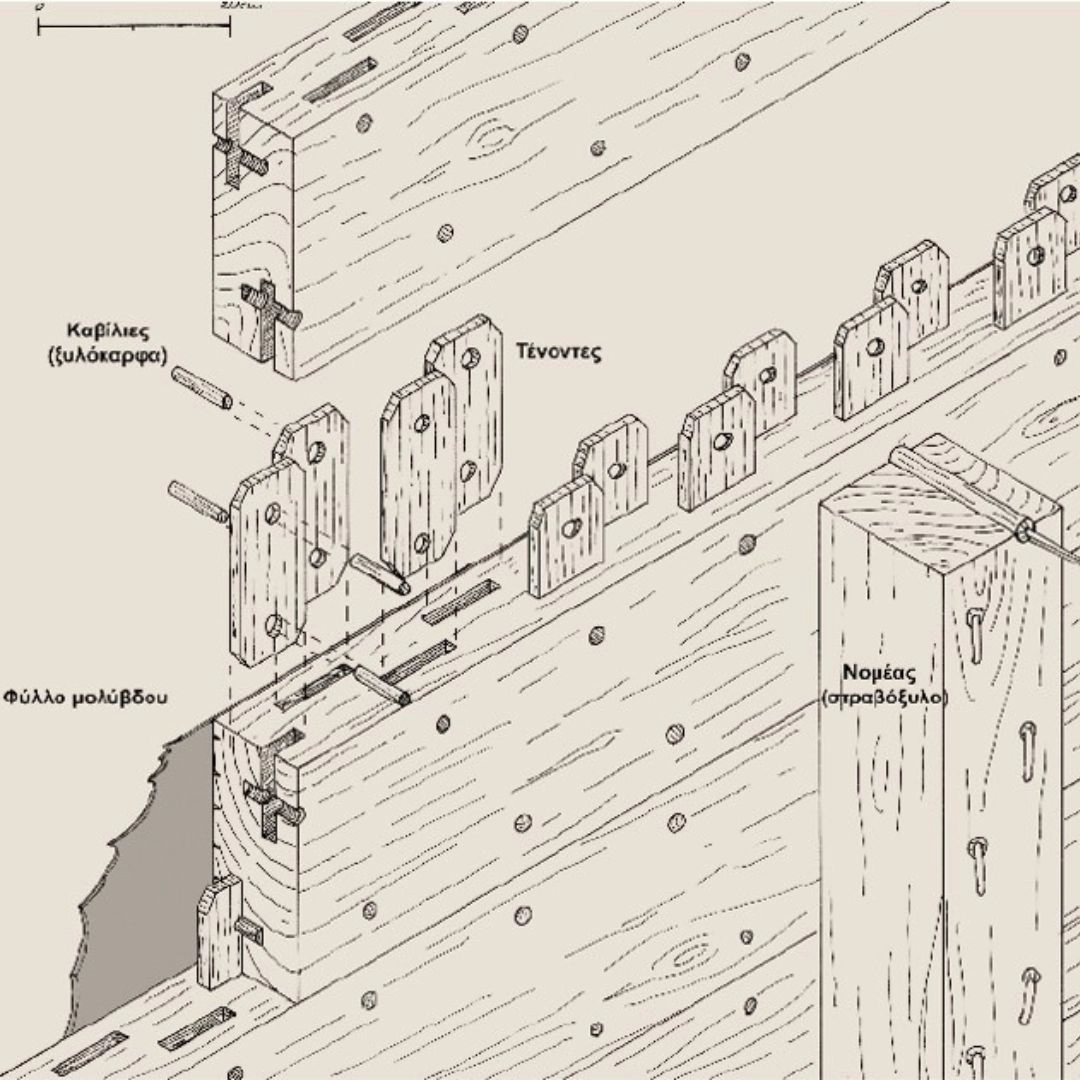

Thanks to the discoveries of underwater archaeology, their shipbuilding method has also become understandable. They first constructed the hull (skin) of the ship and then reinforced it internally with nomes (crossbeams). In other words, there was no skeleton from the beginning, onto which the planks (timbers) of the skin were nailed, as is practiced in modern and contemporary shipbuilding. The joining of the timbers was achieved with indentations (recesses carved into the narrow sides of the timbers) and tormos (wooden pieces that penetrate the indentations), which were secured with wooden pegs (dowels). This technique originated in furniture making and ensured a sturdy and waterproof hull, without the need for caulking.

The ship’s course

The study of the archaeological findings, combined with the location identified in the wreck (stratigraphy), provides some information on which logical hypotheses can be formulated about the course followed by the ship. The excavator has suggested that the port of Piraeus was the place of loading for the black-glazed pottery, as it is likely that it was produced in an Athenian workshop. The city of Mende in Chalkidiki was, of course, an essential stop on the journey, where the wine was loaded into its characteristic amphorae. Another critical stop was Skopelos, also a wine-producing region and the place of production of the Peparithos amphorae. From there, it is possible that the ship was heading towards ancient Ikos (Alonissos) or was leaving from there when it sank, not far from the port.

The causes of the shipwreck

The cause of the shipwreck remains unknown. However, we can rule out a collision with a natural obstacle, as the location of the shipwreck is quite far from the rocky coast. The excavator presents two scenarios based on excavation findings and the historical conditions that prevailed at the time of the shipwreck. The detection of traces of combustion during the excavation could be an indication of a fire. Perhaps, again, the temptation of great profit, due to the particular increase in prices caused by the Peloponnesian War, led to an overloading of the ship, which, in combination with a rough sea or a mishandling, proved fatal.

Whatever the case, the impressive shipwreck of Peristera proved that large merchant ships, over 100 tons, were traveling in the Mediterranean as early as the 5th century BC.

The cargo

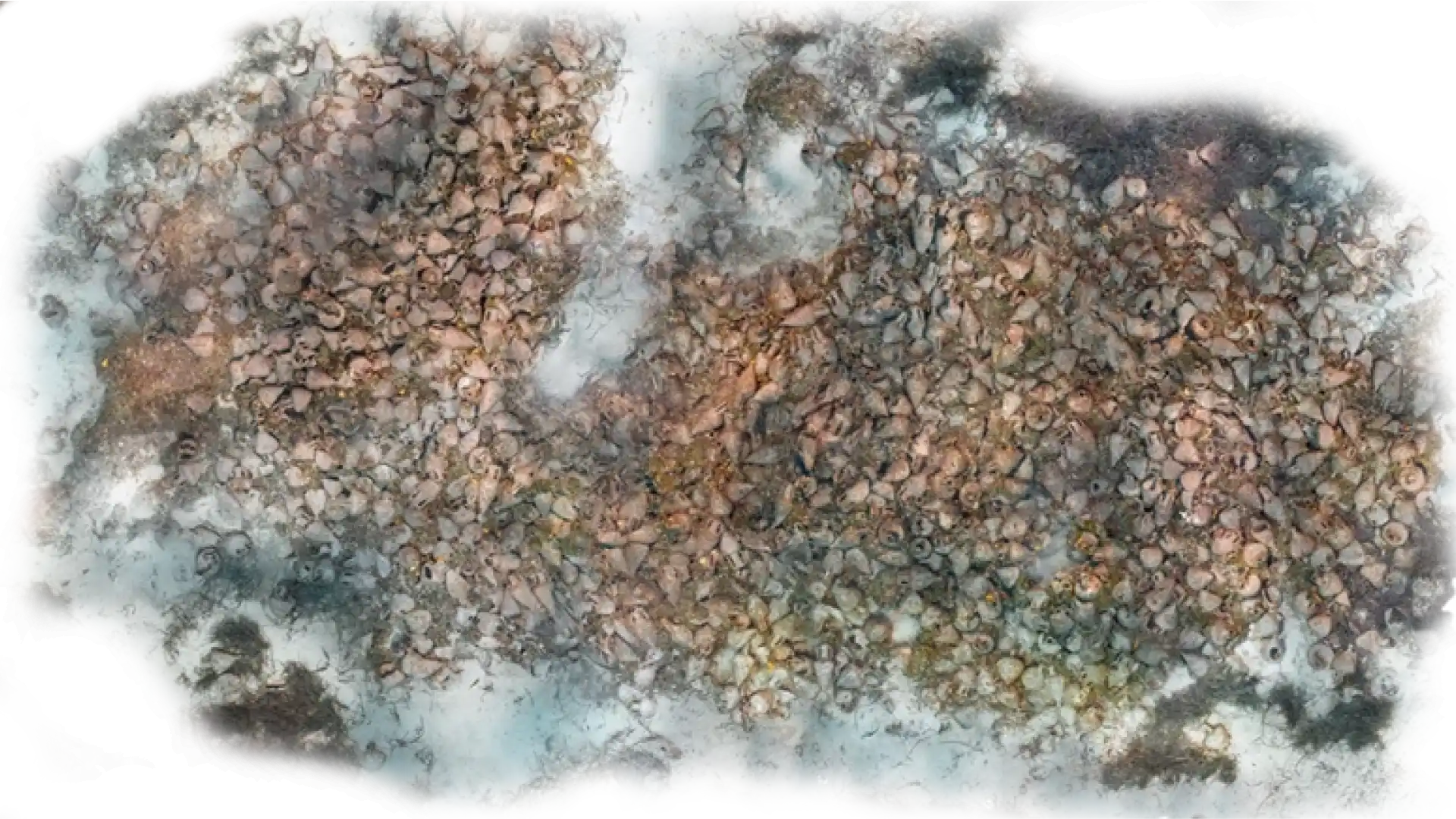

The wreck’s cargo lies on a gently sloping seabed, at a depth of 22 to 30 meters below the surface. It consists of more than 3,000 amphorae originating from two regions known in antiquity for the production and trade of wine.

Mende, a colony of Eretria on the western coast of Chalkidiki, was famous since antiquity for the production of its excellent quality wine, which is also mentioned in ancient sources, such as Athenaeus and Demosthenes. Mende’s wine was exported throughout the Aegean and Mediterranean, contributing significantly to the economic prosperity of the city.

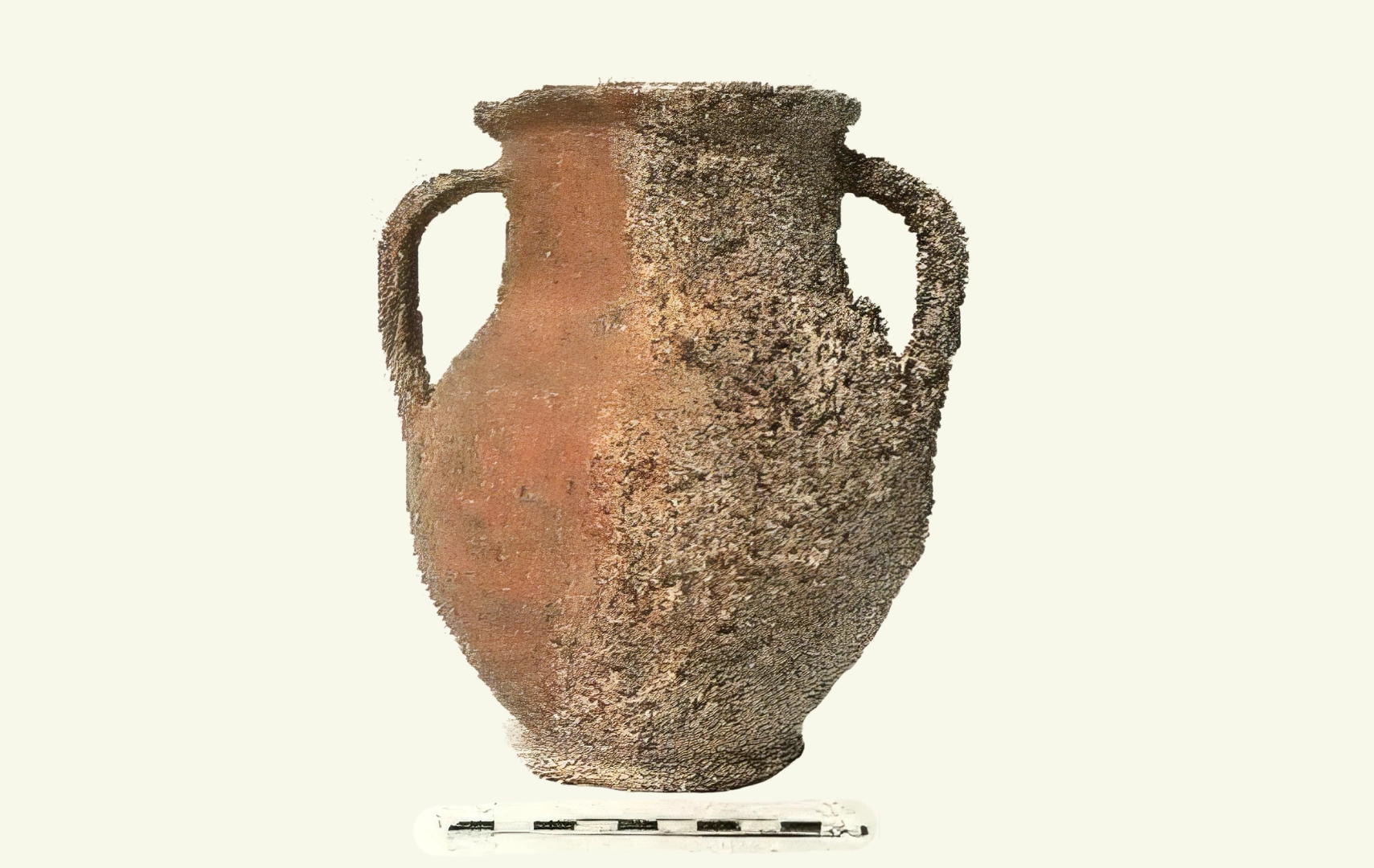

The pointed-bottom “Mende” amphorae served as the region’s main export vessel and were among the most widespread commercial amphora types of the 5th century BC. They are characterized by their elongated shape, narrow neck, curved body, and conical base — features that facilitated stable loading in ship holds and the efficient transport of large quantities of liquid goods.

The specific type of Mendean amphora detected at the Peristera shipwreck has a height of 0.60 m, a capacity of 20 liters, and when full, it weighed approximately 36 kg.

The island of Peparethos (modern Skopelos) is referred to in ancient sources as “eubrotes”, meaning a land rich in abundant and fine grapes. The island developed its own distinctive type of amphora, examples of which have been found in many regions of the Aegean Sea as well as in the Black Sea.

This type of vessel belongs to the category of commercial amphorae that archaeologists describe as pointed-bottomed (oxypythmenoi) due to their shape. This ergonomic base made the amphorae easier to handle and more resistant to stress, but most importantly, allowed for the optimal use of the ship’s storage space. It enabled the amphorae to be loaded in successive layers without leaving significant gaps between them, resulting in a compact cargo that minimized the risk of shifting and potentially dangerous tilting of the ship.

This particular type of amphora from the wreck of Peristera is 0.80m high and weighed approximately 26kg when it was complete with its contents.

In the last stratigraphic arrangement – below the amphorae – rows of finely crafted black-painted banquet vessels of excellent technique were excavated, with the glossy black color, a symbol of their Athenian identity. These are kylices, elegant wine-drinking vessels with pressed and engraved interior decoration that were produced and exported by Attica from 425 BC to about 350 BC, mainly for use in banquets. Found concentrated and without traces of use, elements indicate that they were also intended for trade.

Another part of the cargo consisted of black-painted boards placed in a row one on top of the other, probably in a wooden box, which was not preserved.

Maritime trade in antiquity

In ancient times, as in modern times, the bulk of trade in the Mediterranean region was carried out by sea. The study of shipwrecks, particularly their cargo, is a vital source of information for understanding maritime trade networks, centers of production and movement of goods, as well as economic and cultural interactions between different regions and populations.

Ancient merchant ships often operated in circular or sequential routes, moving from port to port, where they unloaded, exchanged or replaced part of their cargo.

The bulk of maritime transport involved food goods in high demand, such as cereals (mainly wheat), wine, olive oil, fruits, legumes, vinegar and aromatic oils. Grains, fruits, and legumes were transported in jars, but were likely also packed in sacks made of organic materials, which did not survive the journey at sea. In addition to food, ships also transported other items for trade, such as wood, rocks, metals, and precious materials, serving utensils, storage vessels, and even works of art.

The packaging and transport of products were adapted to the nature of each commodity. Some loads were transported in bulk, while others were placed in sacks, pithoi or —mainly— in commercial amphorae. The latter constitute a typological indicator of exceptional importance for archaeological research, as they vary according to the periods, regions and production workshops. The shape, dimensions, sealings, engravings and other decorative or functional elements of the amphorae functioned as means of identifying their origin.

Sharp-bottomed amphorae are the most common type of commercial vessel. They weigh about 8-10 kg and have a capacity of 15-25 litres. They are perhaps among the most cleverly designed and practical transport vessels of antiquity, as they feature two handles that aid in carrying, a narrow, high neck, and a sharp end to allow for safe stowing in the hold.

The underwater world of shipwrecks

When ships are wrecked on the seabed, their transformation into an “artificial reef” begins, and an entire marine ecosystem develops. The process is even more intense when the ship sinks on a sandy bottom, where the rocky relief that favours diverse aquatic flora and fauna is absent.

The end of the ship and its cargo at the bottom attracts the first fish that seek the food released by the disturbance of the seabed. Subsequently, and for a long time, the organic materials and their decomposition constitute a source of food: wood, ropes, sails, food, fruits, etc. Accordingly, the ship’s volume and cargo become a hiding place for permanent habitation. Golden groupers, white groupers and dusky groupers make the dark cavities their home. When the organic materials disappear, octopuses, moray eels and lobsters turn the amphorae into their chambers, setting traps for the fish that sail around the wreck.

Moray eel inside an amphora at the Peristera shipwreck

Bibliography & additional information

- Hadjidaki E. (1996) Underwater Excavations of a Late Fifth Century Merchant Ship at Alonnesos, Greece: the 1991-1993 Seasons. In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique. Volume 120, livraison 2, 1996. pp. 561-593.

- Hadjidaki, E. (1991). The work of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, AD 46 (1991), Chronicles B΄2, Athens: TAPA, 523-524.

- Hadjidaki, E. (1992). The work of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, AD 47 (1992), Chronicles B΄2, Athens: TAPA, 696-699.

- Hadjidaki, E. (1993). The work of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, AD 48 (1993), Chronicles B΄2, Athens: TAPA, 586-587.

- Hadjidaki, E. (1999). The work of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, AD 54 (1999), Chronicles B΄2, Athens: TAPA, 1019-1020.