Remains of shipwrecks mainly from the Byzantine period

Glaros

Cape Glaros, located at the southwestern entrance to the Pagasitic Gulf, is an important underwater archaeological site, often described as a “shipwreck cemetery.” This location is of strategic importance, as the cape served as a guiding point for entering the Pagasitic Gulf.

The remains of at least four ships from different periods have been identified in the area. Specifically, the wrecks of a Hellenistic ship, a Roman ship and two Byzantine ships have been identified. The findings include a multitude of vases and commercial amphorae, which constituted the main cargo of the ships, as well as an impressive set of anchors of various types and periods, which reveal the evolution of shipbuilding and maritime practices over the centuries.

Discoveries at the bottom of Glaros: Anchors, amphorae and stories from the Byzantine era

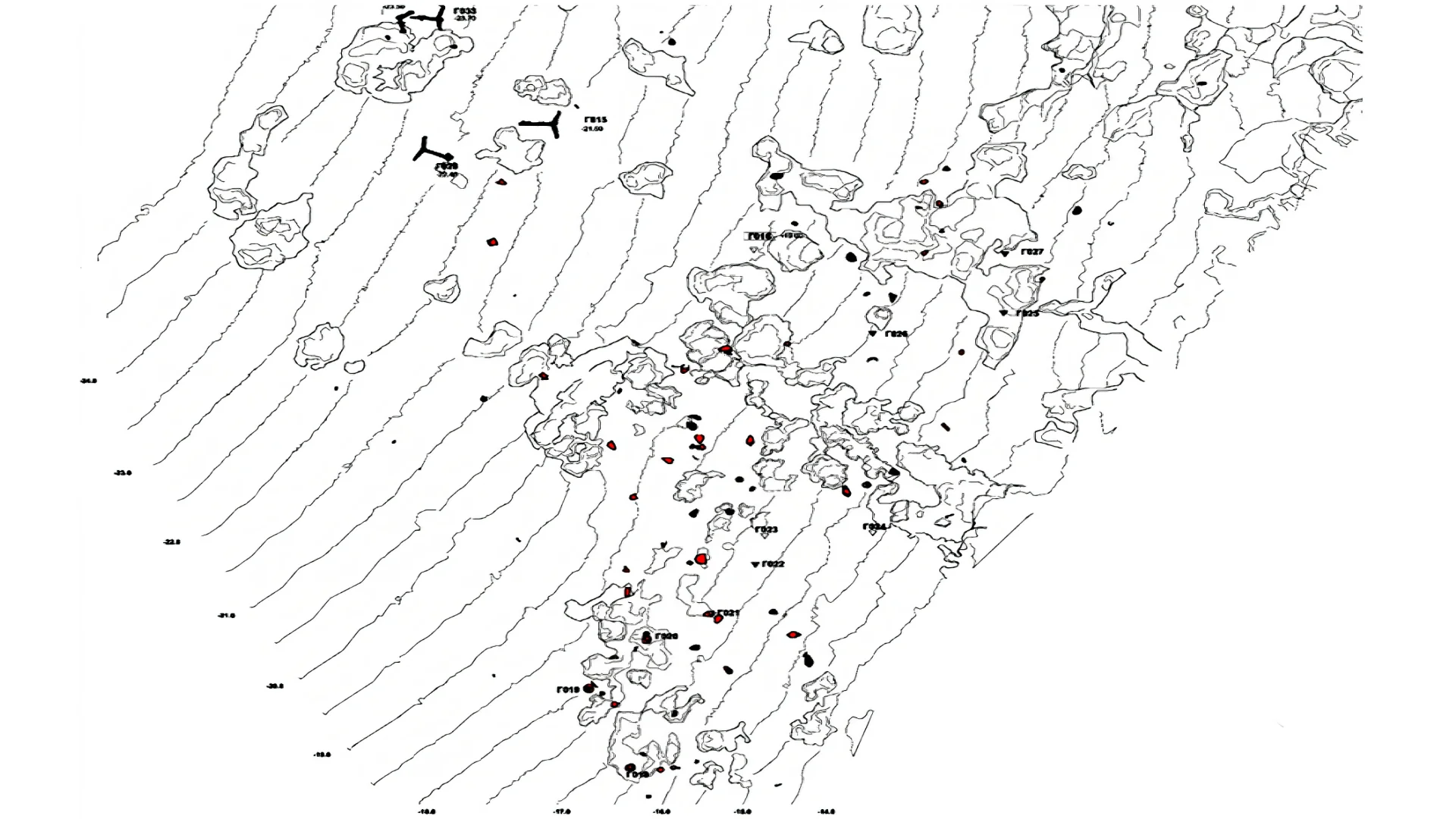

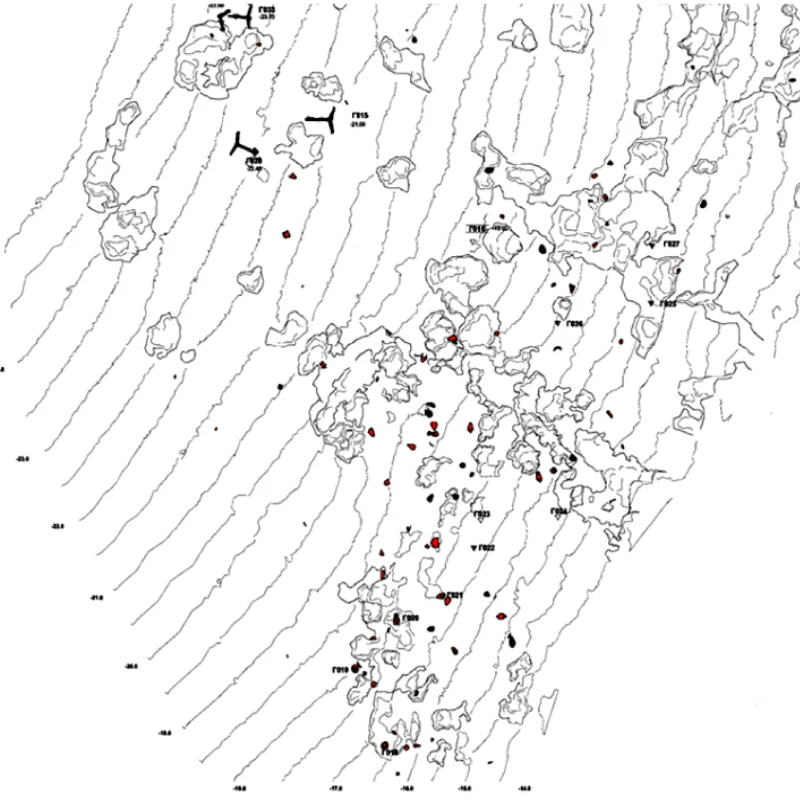

The Glaros AUAS is located on the NW side of the cape of the same name, which extends along the SW coast of the Pagasitic Gulf, in Sourpi, Magnesia, forming a large and fairly weather-protected bay – the Nies Bay. The Glaros AUAS occupies an area of approximately 2,000 sq.m., with a maximum depth of -27m. and is part of the declared underwater archaeological site of Glaros, which includes the northern and eastern coast of the cape (Government Gazette 1028/Β/2004 & Government Gazette 270/ΑΑΠ/2014).

Cape Glaros is characterized by a hill with dense low vegetation that ends in inaccessible, rocky shores. Its slopes continue below sea level with a fairly steep slope, and meet the sandy bottom at depths greater than -20m.

Its location at the entrance of the bay of Nies, but also near the entrance of the Pagasitic Gulf, certainly made the Cape of Glaros frequent for ancient and Byzantine merchant ships.

Witnesses to this activity and to the navigation of the region in general, as well as to the dangers it entailed, are the remains of ancient shipwrecks from different periods, a fact that has given Cape Glaros the designation of “cemetery of ancient shipwrecks”. Specifically, at least 4 shipwrecks from the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine periods have been identified. The findings include a multitude of commercial amphorae and an impressive set of anchors of various types, characteristic of the evolution of this essential naval accessory from prehistoric to Byzantine times.

The research

In the maritime area of the AUAS and Cape Glaros in general, the IENAE, under the supervision of the EUA and the direction of the diving archaeologist Elias Spondylis, carried out underwater reconnaissance research during the years 2005-2006, 2008 and 2014-2015. The result was the identification and documentation of remains of ancient and Byzantine ships.

The finds include anchors and amphorae of various types and periods, however the most important date back to the end of the Middle Byzantine period (12th century), with the most impressive being the large iron anchors, which in fact constitute the largest such set discovered in Greece.

The anchors

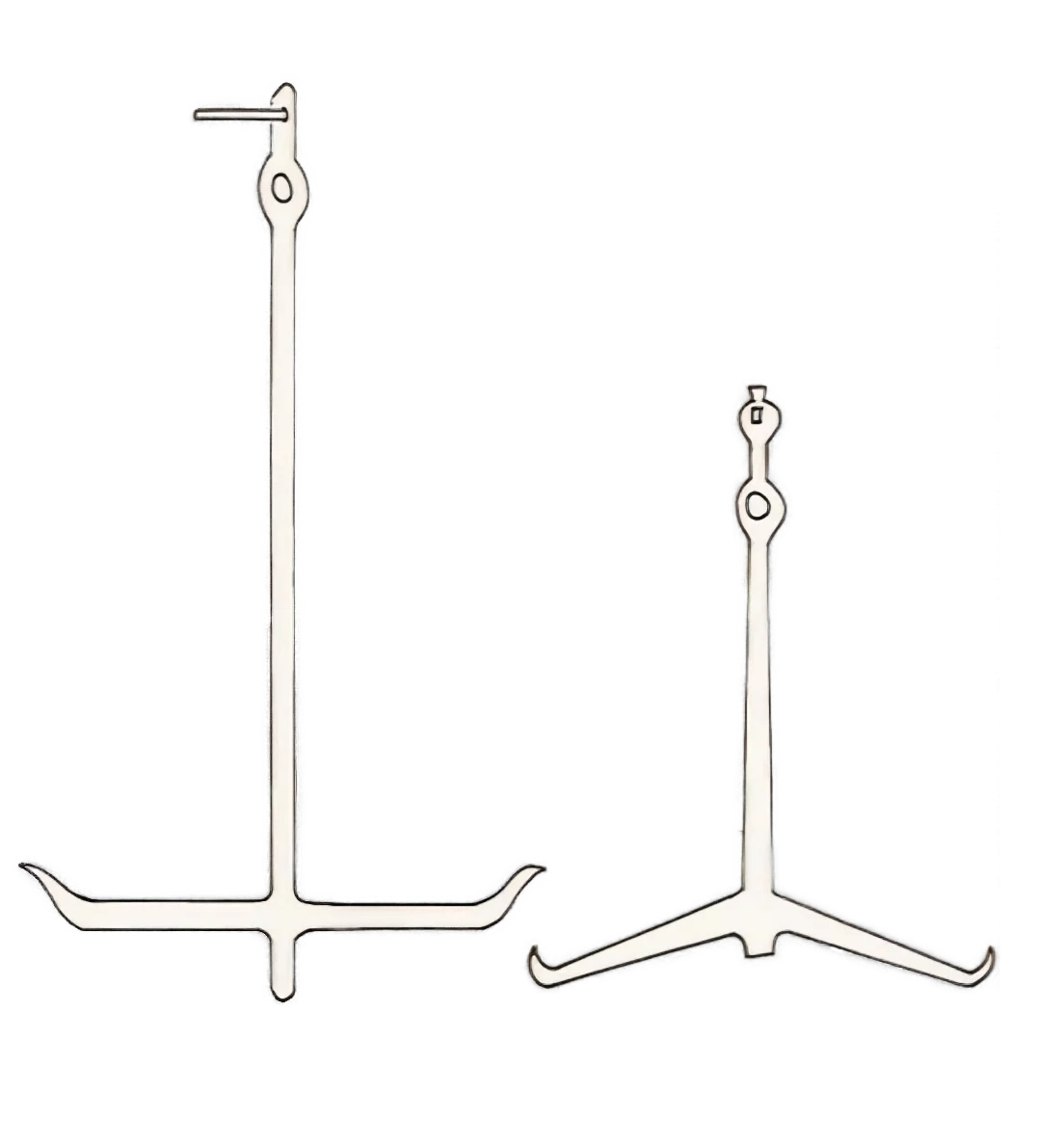

The anchors that have been identified at the Glaros AUAS exceed twenty and belong to four known types of ancient anchors that represent important stages in the evolution of a component so essential for the safety of every ship.

The first and oldest type belongs to the type of triangular (or trapezoidal) stone anchor with holes, one for the rope and two for the fastening of wooden hooks (nails). This type appears at least from the 2nd millennium BC and probably corresponds to the term “euni” mentioned by Homer in the Iliad. Despite the establishment of more technologically advanced anchors from the archaic years onwards, the use of this anchor continues throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, and is even attested in the 20th century! 2 samples of this type have been identified in the AUAS of Glaros, but as they are not related to other finds, their dating remains uncertain.

The second type belongs to the type of wooden anchor with a stone head – the horizontal stem that ensures the effective anchor position on the bottom. This advanced type appears in the archaic era (around the middle of the 7th century BC) and bears all the morphological characteristics that will be established in the known form of the anchor until modern times. As the remaining parts of the anchor were wooden and therefore were not preserved in the underwater environment, the only trace that testifies to their presence on the bottom is their stone head. 4 stone heads have been identified in the Glaros AUAS.

The third and fourth types belong to the last evolutionary stage of ancient and medieval anchors, which are iron anchors. Although their construction is attested as early as the 5th century BC (Herodotus), their use will become widespread from the first post-Christian centuries (2nd -3rd century) onwards. Of the six (6) main types into which iron anchors are typologically classified according to the most recent classification (Haldane), the last two are represented in Glaros chronologically, T-shaped and Y-shaped respectively. T-shaped anchors have been used as early as the 7th century (Jassi Ada shipwreck), while Y-shaped anchors seem to appear during the 10th century. They were certainly in use at the beginning of the 11th century, as shown by the well-dated shipwreck at Serce Limani (1025).

More recent research has shown that the two types are found together on ships from the late middle Byzantine period, a finding reinforced by the anchors at Glaros, as they appear to belong to a shipwreck of a merchant ship that was carrying Byzantine amphorae from the 12th century.

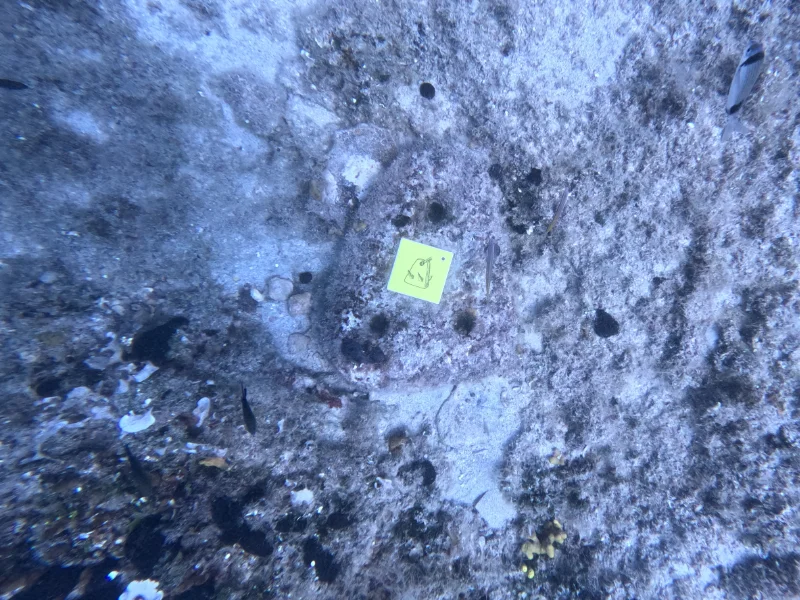

In the Glaros AUAS, 18 iron anchors have been identified, constituting the largest set in Greece. Most of them are largely intact (except for the stipules), but they are severely corroded and their surface is completely covered by biogenic deposits.

Their size is typical of a large merchant ship.

They form two main concentrations, approximately 50 meters apart, but they could belong to the same ship, as we know that ships of the time were equipped with multiple anchors, so that they could replace those that were lost or deliberately abandoned.

The amphorae

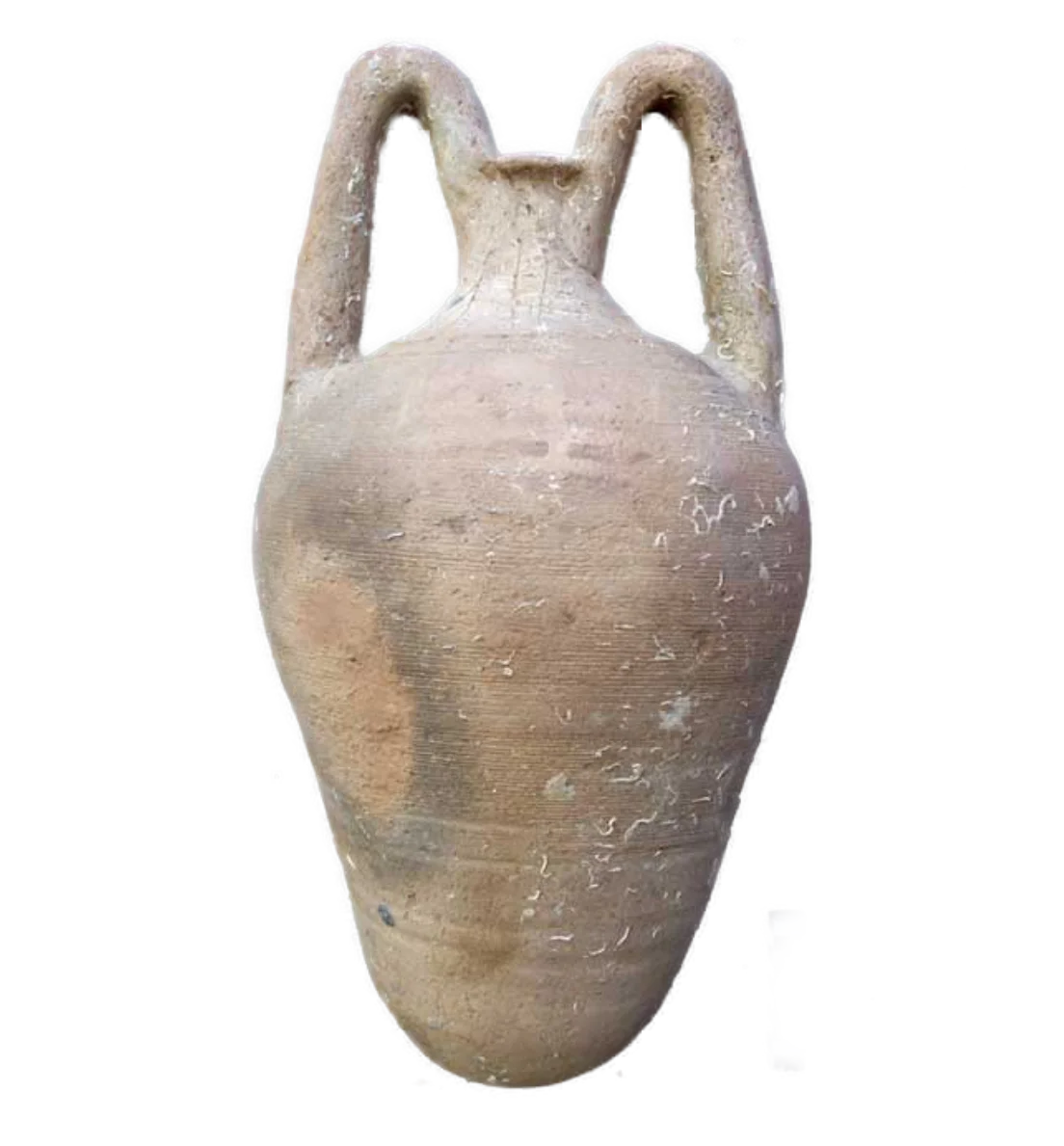

Until the definitive prevalence of wooden barrels, which occurred at least in the eastern Mediterranean in the 14th century AD (at the end of the Byzantine era), the main container for storing and transporting products – especially liquids – was clay commercial amphorae. These amphorae are distinguished by their large capacity, their unadorned and generally less elaborate appearance, and the characteristic sharp end of their base (hence the name oxypythmenoi), which particularly served their loading and safe transport in the holds of ships. During the Byzantine period, the term “magarikon” was used as a synonym for “amphora”, attested from the 6th to 7th centuries. The word is a corruption of “Megarikos”, which originally denoted an amphora with a clear place of origin, but later came to mean any amphora.

In the Glaros AUAS, a multitude of commercial amphorae have been identified that ended up on the seabed from shipwrecks or even because they were simply discarded by passing boats (usually these are isolated finds).

The oldest examples of Glaros amphorae date from the late 3rd to the mid-2nd century BC (Hellenistic period), some from the late 1st to the early 2nd century BC (Early Roman period) and others from the 4th to the 6th century AD (Late Roman period). These periods, however, are represented by few examples.

Most of the amphorae date from the 12th century, at the end of the Middle Byzantine period. Although they have not preserved the arrangement they would have had when loaded and are mostly broken, their density indicates that they were the cargo of (at least) a shipwreck of this period, as is also suggested by the iron anchors near which they are found.

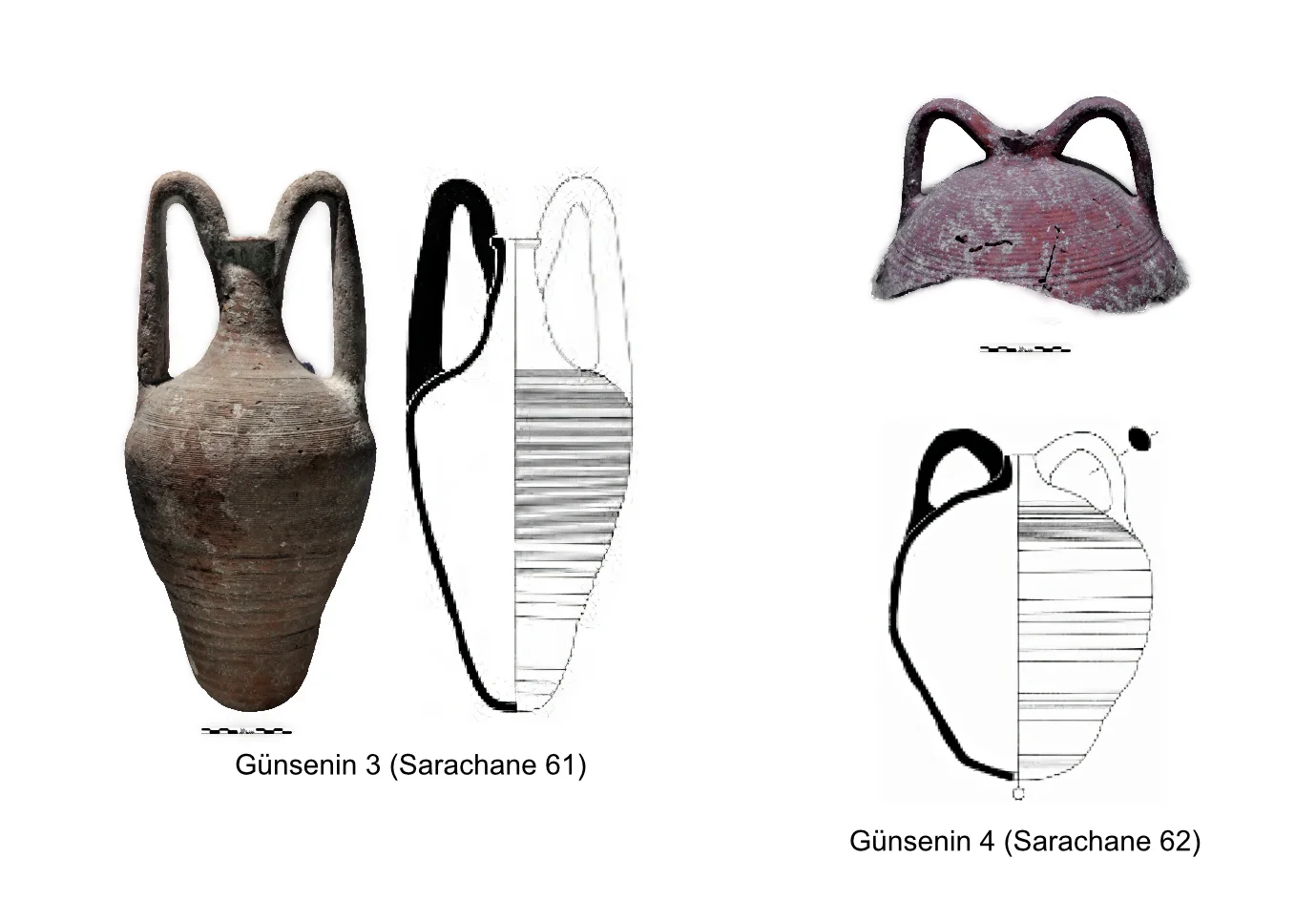

They are distinguished into two types of amphorae that often coexist in shipwrecks and are the characteristic vessels for transporting oil and wine during the 12th century, with widespread distribution in the empire.

The first type belongs to the 5th group of Bakirtzis’ Magaric, but is also known in the literature under the names Gϋnsenin 3 and Sarachane 61. It is an amphora with an elongated, almost spindle-shaped body that bears horizontal grooves, a tall, narrow neck and strong, high handles that extend well beyond the mouth.

Bibliography & additional information

- Koutsouflakis G. 2018: “Ancient anchors from the seabed of the South Evian Sea”, in “Dive into the past: Underwater Archaeological Research 1976 – 2014”, published by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, pp. 125-152

- Haldane D. 1990, «Anchors of Antiquity», The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 53, No. 1, An Underwater View of the Ancient World (Mar., 1990), pp. 19-24 Published by: The American Schools of Oriental Research (διαθέσιμο στο διαδίκτυο: Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3210149)

- Demesticha-Spondylis 2011:_LR-Byz. Trade at the Aegean – Pagasitikos Wr. 7 SKYLLIS, σ.37-39.

- Spondilis, Michalis: ITACA’s Test Case Greece: The Pagasetikos Underwater Archaeological Research at Metohi and Glaros, ΕΝΑΛΙΑ ΧΙII, 2018, σ.90.