Byzantine period shipwreck

Agios Petros (Kyra Panagia)

In 1970, in the bay of Agios Petros in Kyra Panagia (also known as Pelagonisi), an impressive Byzantine shipwreck was discovered dating back to the mid-12th century AD. The ship, with estimated dimensions of 25×8 meters and a displacement of at least 100 tons, is a valuable piece of the maritime history of the Aegean.

An important Byzantine shipwreck

In 1970, in the bay of Agios Petros in Kyra Panagia (also known as Pelagonisi), an impressive Byzantine shipwreck was discovered dating back to the mid-12th century AD. The ship, with estimated dimensions of 25×8 meters and a displacement of at least 100 tons, is a valuable piece of the maritime history of the Aegean.

The dimensions of the ship were estimated at 25×8 meters, with a displacement of at least 100 tons. The ship’s cargo included commercial amphorae, numerous glazed tablets with elaborate engraved decoration, six millstones, as well as small quantities of lamps, amphorae, jars, pithoi and glass vials.

The discovery

Oral testimonies indicate that the Byzantine shipwreck in the bay of Agios Petros was discovered in the early 20th century by sponge divers, just like the classical shipwreck of Fagros at the entrance to the same bay. During the 1960s, it gained intense publicity due to the case of its extensive looting by foreign antiquities smugglers, which was revealed with the confiscation of excellent quality Byzantine paintings from the 12th century AD.

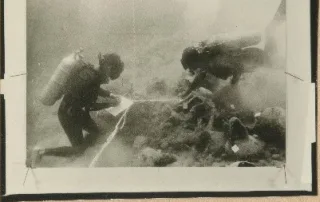

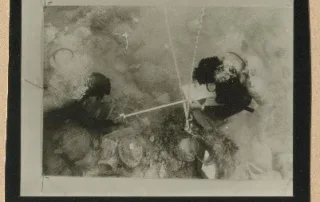

These events contributed to the decision of the General Directorate of Antiquities to carry out an underwater archaeological survey. The excavation was carried out under the direction of archaeologists Katerina Romiopoulou and Charalambos Kritzas, in collaboration with P. Throckmorton as technical director, marking the first large-scale underwater archaeological survey in Greece, even before the establishment of the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities.

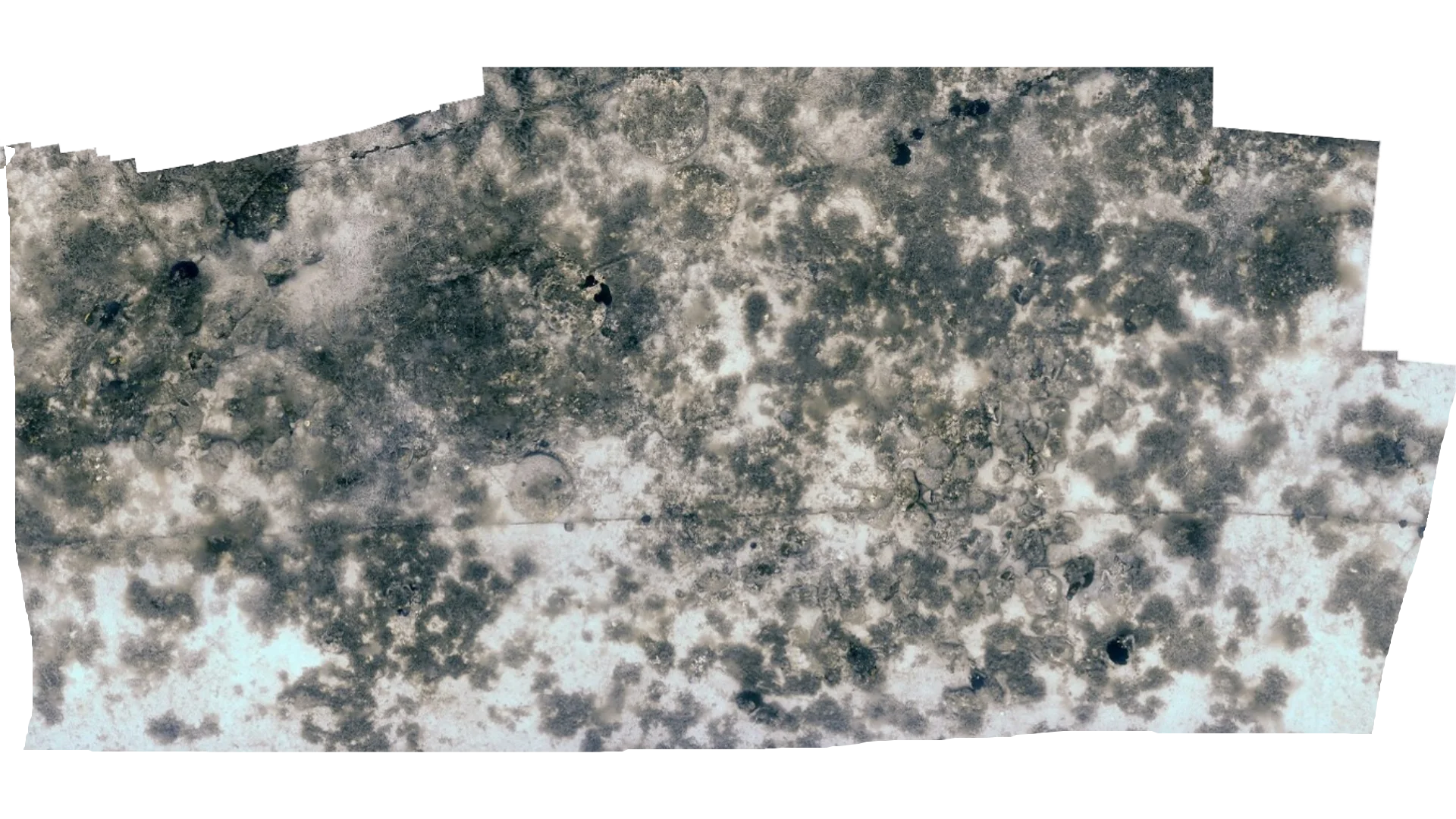

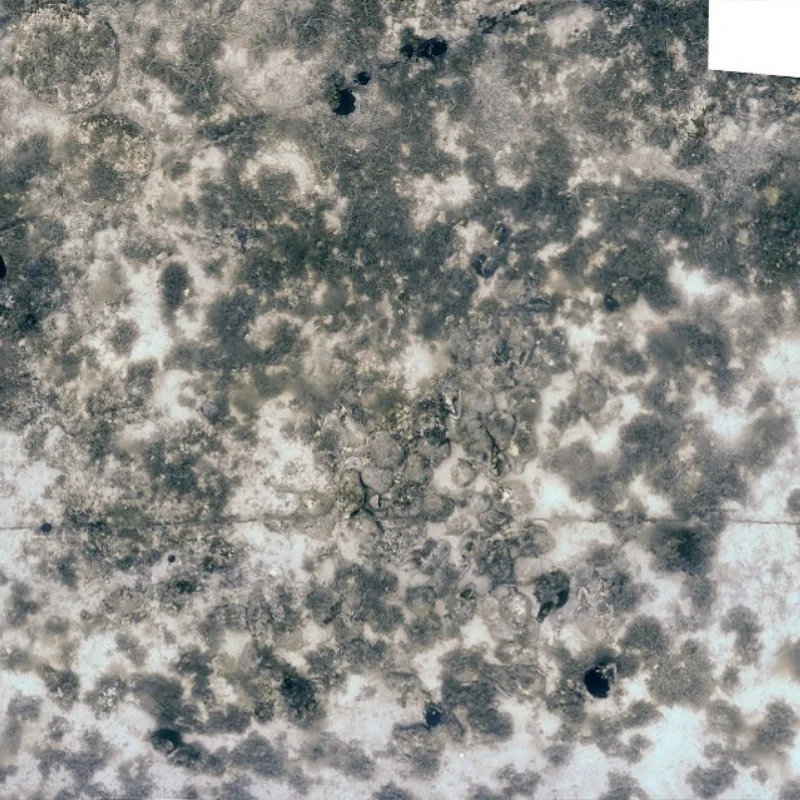

The research was carried out in the summer of 1970 and evolved into two phases. Initially, the wreck was photographed by creating a photomosaic, while sample extractions were also carried out. Subsequently, most of the ceramic finds were extracted and two test cuts were made, which revealed preserved parts of the ship’s wooden structure, such as the spars and the skin.

The ship

The shipwreck of Agios Petros is an important testimony to Byzantine navigation and trade in the Aegean region during the 12th century AD. From the dimensions of the surviving parts, it is estimated that the ship had dimensions of 25×8 meters and a displacement of at least 100 tons. During the reconnaissance survey, a large part of the ship’s hull was found in good condition.

The cargo

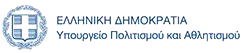

The ship’s cargo included six large granite millstones and commercial amphorae of the Günsenin III type, in two variants. These represent one of the most widespread amphora types of the Middle and Late Byzantine periods. The same amphorae were classified by Bakirtzis into the 5th group of “magaric” amphorae, a testament to their wide distribution and diverse production.

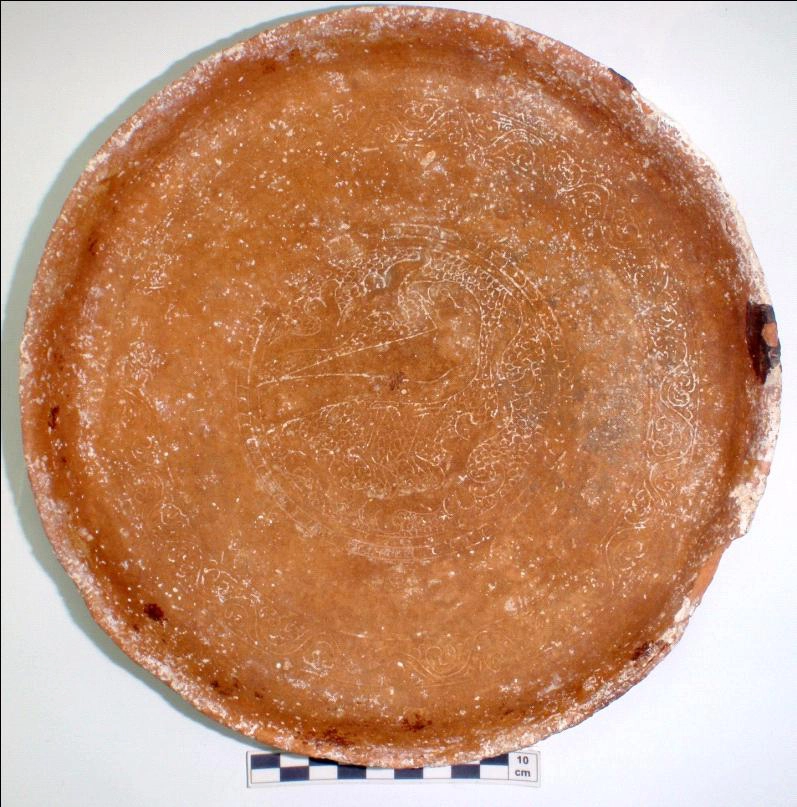

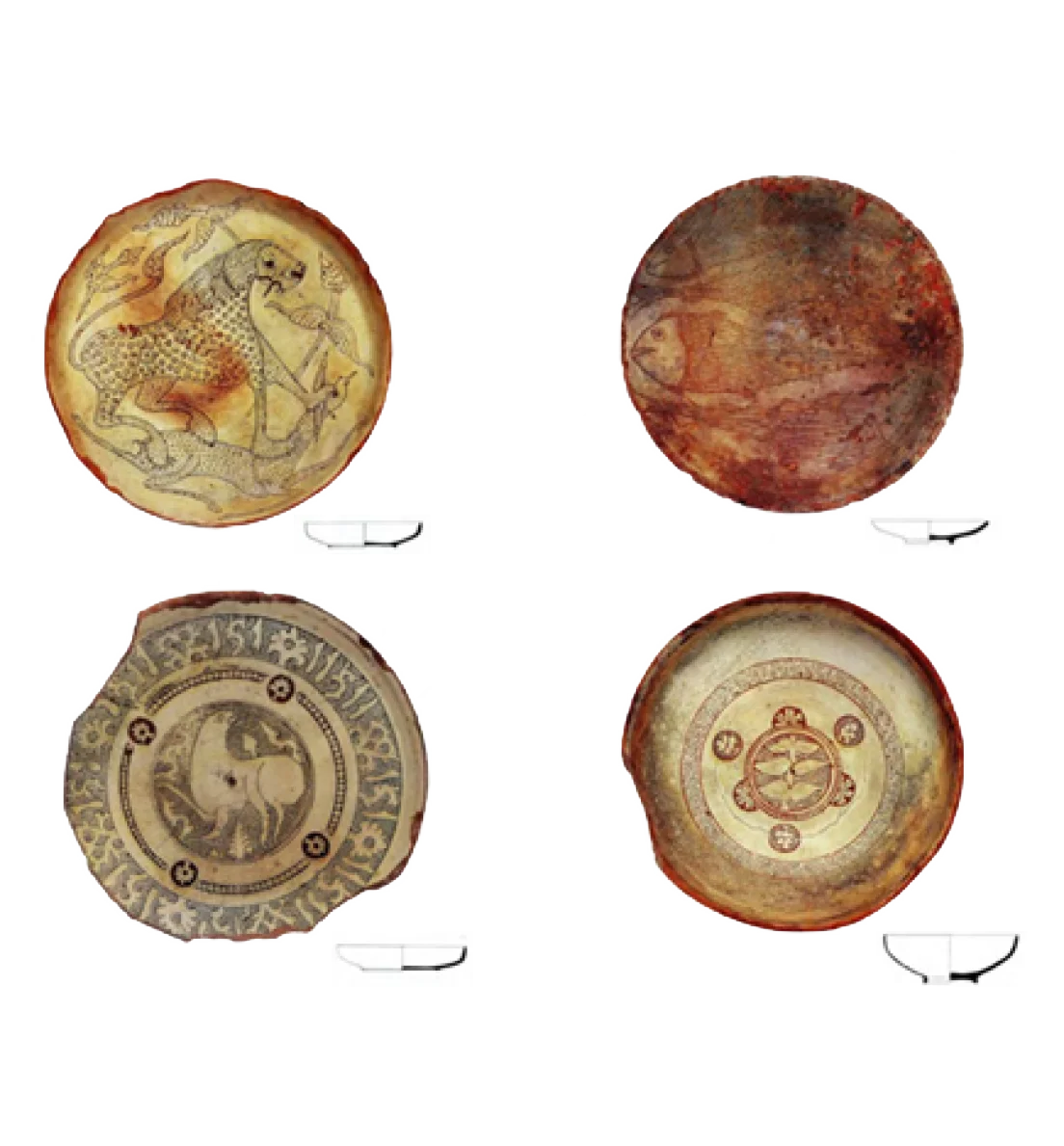

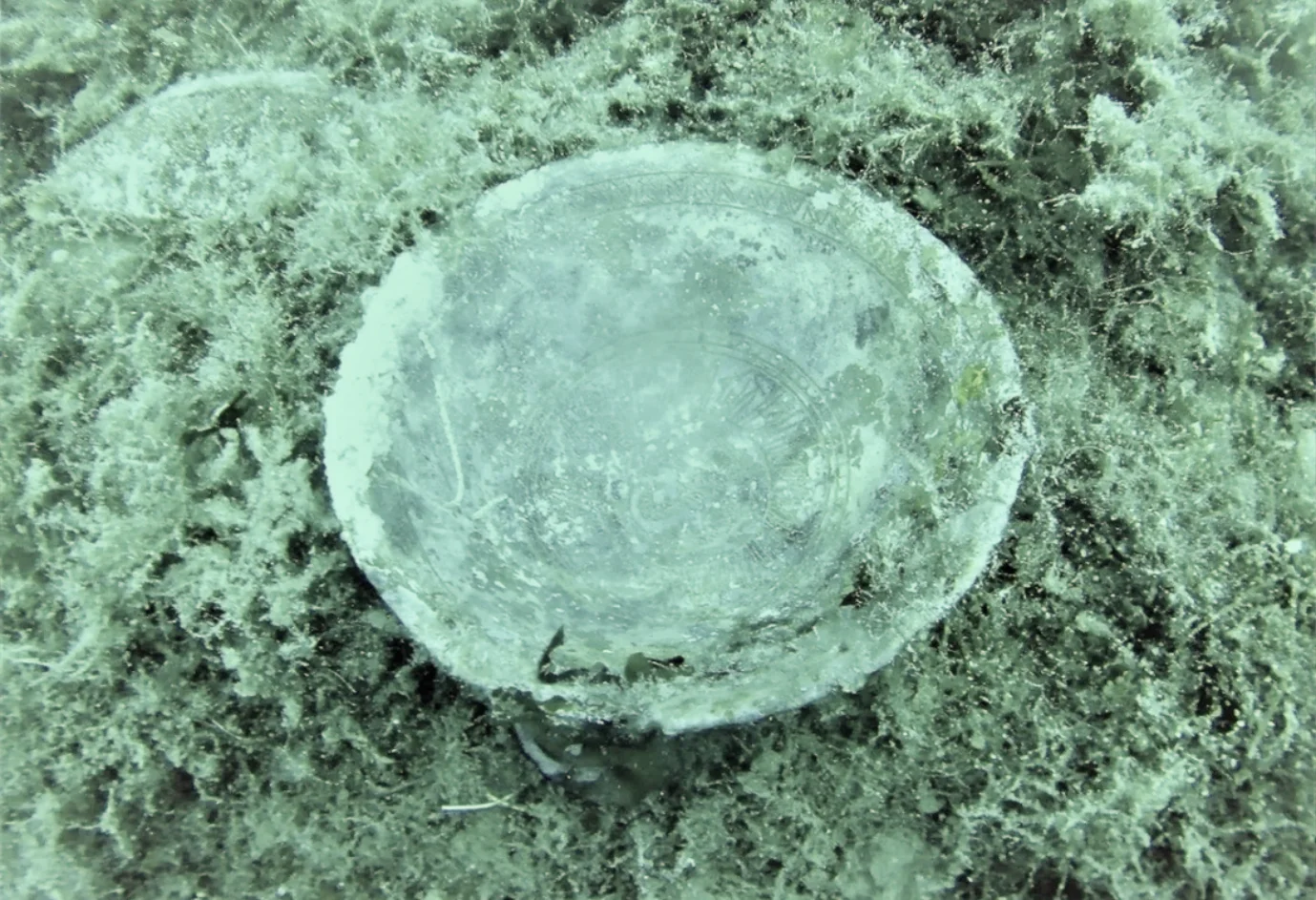

In addition, more than 700 glazed plates (sgraffito ware) with elaborate incised decoration were found, featuring geometric motifs as well as representations of plants and animals — both real and mythical.

Objects found in smaller quantities — such as lamps, small amphorae, jugs, storage jars (pithoi), glass vials, lids of wide-mouthed vessels, and a fragmented bronze cauldron — may be attributed to the ship’s equipment. Traces of both the 1970 archaeological investigation, such as a section of the perimeter line made of polypropylene, and of subsequent looting by antiquities thieves are also visible on the site, including clear breakages of amphorae and plates.

Günsenin III type amphorae, also known in Greek scholarship as “Magaric” (Group V according to Bakirtzis), represent the late Middle and Late Byzantine maritime trade at its highest volume. They formed the main part of the cargo of the Agios Petros/Pelagonnesos wreck.

Despite variations in shape, Günsenin III amphorae share common morphological features, such as an elongated body, narrow neck, and two vertical handles.

Cargoes of this type are usually homogeneous, lacking the presence of other amphora types within the same ship, suggesting an organized trade of specific goods.

Type III is by far the most common Byzantine amphora in the western Aegean. Its wide distribution in shipwrecks and coasts throughout the Aegean testifies to their key role in the commerce of the time.

The cups and plates that formed part of a heterogeneous cargo were decorated using the sgraffito technique on a white or off-white slip. The decoration, confined to the interior surface, was executed through fine incisions. The main decorative themes include freely rendered animal figures and geometric motifs — primarily spirals developed in a central medallion or bands running along the rim.

The glazed plates decorated with representations of animals — both real and mythical — are characteristic examples of 12th-century Byzantine ceramics. They were probably used in ritual, decorative, or utilitarian contexts, reflecting the artistic expression of the period. The widespread distribution of similar plates in regions such as Thessaloniki, Athens, Constantinople, and Crimea highlights the intense movement of commercial goods and artistic products across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Plates featuring vegetal motifs are emblematic of 12th-century Byzantine ceramic production. Their decoration includes intricate relief or incised designs of plants, flowers, and branches, often combined with geometric or animal elements. They were likely used for decorative or ritual purposes while also serving practical functions in daily life.

The plates with geometric designs date to the same period (12th c. AD) and are characterized by the use of repetitive patterns and carefully executed decoration. Despite the relative simplicity of their motifs compared to those with animal representations, their precise geometric ornamentation demonstrates the technical mastery of Byzantine potters and the aesthetic sensibilities of the era.

Maritime trade in antiquity

In ancient times, as in modern times, the bulk of trade in the Mediterranean region was carried out by sea. The study of shipwrecks, particularly their cargo, is a vital source of information for understanding maritime trade networks, centers of production and movement of goods, as well as economic and cultural interactions between different regions and populations.

Ancient merchant ships often operated in circular or sequential routes, moving from port to port, where they unloaded, exchanged or replaced part of their cargo.

The bulk of maritime transport involved food goods in high demand, such as cereals (mainly wheat), wine, olive oil, fruits, legumes, vinegar and aromatic oils. Grains, fruits, and legumes were transported in jars, but were likely also packed in sacks made of organic materials, which did not survive the journey at sea. In addition to food, ships also transported other items for trade, such as wood, rocks, metals, and precious materials, serving utensils, storage vessels, and even works of art.

The packaging and transport of products were adapted to the nature of each commodity. Some loads were transported in bulk, while others were placed in sacks, pithoi or —mainly— in commercial amphorae. The latter constitute a typological indicator of exceptional importance for archaeological research, as they vary according to the periods, regions and production workshops. The shape, dimensions, sealings, engravings and other decorative or functional elements of the amphorae functioned as means of identifying their origin.

Sharp-bottomed amphorae are the most common type of commercial vessel. They weigh about 8-10 kg and have a capacity of 15-25 litres. They are perhaps among the most cleverly designed and practical transport vessels of antiquity, as they feature two handles that aid in carrying, a narrow, high neck, and a sharp end to allow for safe stowing in the hold.

Bibliography & additional information

- Kritzas, Ch. (1971). The Byzantine Shipwreck of Pelagonisos – Alonissos, Athens Annals of Archaeology IV. 2, 176-182.

- Kritzas, Ch. & Throckmorton, P. (1991). An Odysseus of the Deep, Enalia, Suppl. 2, IENAE.

- Mavrikis, K. (1997). Ano Magniton Islands, 311-317.

- Bakirtzis, Ch. (2003). Byzantine Tsoukalolagina, Athens.

- Dina, A. (1999). The Byzantine shipwreck of Pelagonnisos, Alonissos, 122-142 in D. Papanikolas-Bakirtzi (ed.), Byzantine Glazed Ceramics, Athens 1999.

- Tagonidou, Aik. (2018). The shipwrecks of the National Marine Park of Alonissos, Northern Sporades, in A. Simosi (ed.), Dives into the Past: Underwater Archaeological Research, 1976 – 2014, Athens: TAPA, 159-161.

- Ioannidaki-Dostoglou, E. (1989). “Les vases de l’épave byzantine de Pélagonèse Halonnèse,” in Déroche & Spieser 1989, pp. 157–171.

- Koutsouflakis, G. (2020). “The transportation of amphorae, tableware, and foodstuffs in the Middle and Late Byzantine period: The evidence from Aegean shipwrecks,” in S.Y. Waksman (ed.), Multidisciplinary Approaches to Food and Foodways in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean, Archéologie(s) 4, Lyon, pp. 447–481.

- Papanikola-Bakirtzi, D. (1999). Byzantine Glazed Ceramics: The Art of Sgraffito, Athens.

- Parker, A.J. (1992). Ancient Shipwrecks of the Mediterranean and the Roman Provinces, BAR International Series 580, Oxford.

- Throckmorton, P. (1971). “Exploration of a Byzantine wreck at Pelagos Island near Alonissos,” Athens Annals of Archaeology 4 (1971), pp. 183–185.